Authors: Redmond Burke, MD, Cardiovascular Surgery Chief and Anthony Rossi, MD, Chief, Cardiovascular Medicine.

Introduction:

The Heart Institute at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital remains dedicated to providing the very best and safest experience for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery. This report will review the program’s 24-year surgical experience in repairing children with a diagnosis of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).

Methods:

We reviewed our CardioAccess database for patients undergoing repair of TOF from September 1995 through February 2019. Patients included were those with associated AV canal defects and those with TOF and absent pulmonary valve. Patients with TOF/Pulmonary atresia are not included in this report.

Operative digital imaging of each patient’s procedure was routinely used to document the anatomy and repair of each lesion. Every operation was videotaped with a camera at the head of the operating table. The video was visible to the entire team during the procedure and was digitally stored for on-demand performance review. Daily patient images are taken with digital cameras at the bedside by the surgical nurse practitioners. These images are stored chronologically in the EMR, to provide visual documentation of each patient’s preoperative condition, and postoperative recovery.

Clinical Surgical Pearls, Redmond Burke 2019:

Infant repair of TOF is performed with bicaval cannulation via the right atrial appendage and the IVC/atrial junction, and a vent is placed in the left atrium. The branch pulmonary arteries are controlled with tourniquets. The RV is inspected to confirm the coronary anatomy. Two 6-0 Prolene stay sutures are placed in the infundibulum, and an 11 blade is used to enter the right ventricular cavity. The incision is never more than half the length of the RVOT. Muscle bundles are resected with tenotomy scissors and the incision is extended up to within a few mm of the pulmonary valve annulus. Parietal muscle bundles are visualized by placing the patient in Trendelenburg position and rolling the table toward the surgeon. The VSD is inspected and a glutaraldehyde-treated native pericardial patch is trimmed to the correct shape. A running 7-0 Prolene suture is used to secure the patch to the VSD, taking small endocardial bites, beginning at each arm at the papillary muscle of the conus and sewing toward the surgeon, staying within 2 mm of the aortic valve annulus. No pledgets or interrupted sutures are used. The pulmonary valve is inspected and sized with Hegar dilators. Fused commissures are split with an 11 blade. Pulmonary valve preservation is a priority, but not at the expense of an RV pressure greater than half systemic. If the pulmonary valve is too small, a transannular incision is made to the bifurcation of the pulmonary arteries, and this incision is closed with a single pericardial patch and running 6-0 Prolene. We do not create artificial pulmonary mono-cusps or leaflets.

Neonatal repairs are performed with an identical technique except for the suture size, which is reduced to running 8-0 Prolene for the VSD patch, and 7-0 for the RVOT patch. A probe patent PFO is left intact, and a larger ASD is partially closed.

Redmond Burke, as taught by Aldo Castaneda, John Mayer, Richard Jonas and Frank Hanley

Results:

There were a total of 394 neonates, infants and children who underwent repair of TOF during this time period. There were 17 patients who had TOF and AV canal defects and 11 with TOF and absent pulmonary valve. There were 2 hospital deaths (99.5% survival). The median weight at the time of surgery for these children was 6 kgs (range 1.3-44.5kg). There were 28 patients <3 kg and 14 <2.5 kg at the time of complete repair. Patients were operated on at a median age of 123 days. There were 36 neonatal repairs. The median postoperative stay was 6 days. Cardiopulmonary bypass times averaged 108 minutes. Aortic cross clamp time was 68 minutes.

There were no patients who experienced postoperative heart block and required a permanent pacemaker.

| Category |

Number of Patients |

Median Age (d) |

Number of Mortalities |

Percent Mortality |

STS7

Mortality |

NCH Postop LOS |

STS Postop LOS |

| Repair TOF |

394 |

123 |

2 |

0.5% |

1.2% |

6 |

12 |

Discussion:

In May 1945, Alfred Blalock and Helen Taussig reported a series of three children with cyanotic heart disease secondary to diminished pulmonary blood who manifested significant clinical improvement after receiving an operation that created an “artificial ductus arteriosus”1. That report was followed by Dr. Blalock’s remarkable experience performing operations on 110 children with similar pathology. Although almost a fourth of these patients died, it is important to remember that this was an era prior to echocardiography or cardiac catherization2. Clinical suitability for this type of palliation was based on the degree of cyanosis and “the absence of pulsations in the hila of the lungs during fluoroscopic evaluation.”

The first series of patients who underwent successful intracardiac repair of TOF was published by Lillehi et al. in 19553. In this series of ten patients, the VSD was closed primarily (there was no VSD patch) and the operations were performed utilizing cross circulation (this was an era before the heart-lung machine was available).

Repair of tetralogy as we know it today was probably first described in a report by Dr. Castaneda et al in 19654. During this era, an age of 4 years and a weight of 15 kilograms were thought to be the ideal age and size for this operation. Primary infant TOF repair was then advocated by Barratt-Boyes in 1973, when 25 infants and young children, between the ages of 4 months and 2 years underwent repair with only one mortality5.

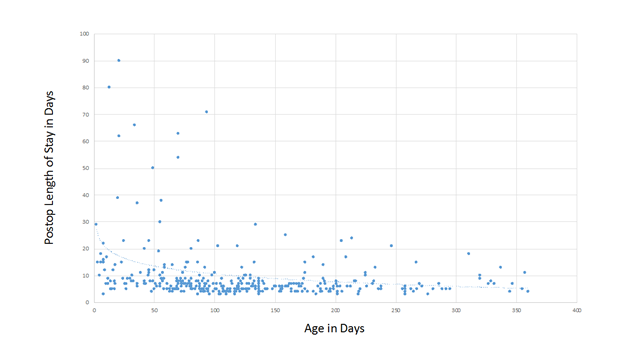

Neonatal repair of TOF is commonplace in some centers today and outcomes for these patients appear to be excellent in the right hands6.; Our series includes 36 patients who underwent primary repair of TOF in the neonatal period, with no mortality. We have found that postoperative length of stay is inversely related to the age at repair (figure 1), although the median length of postoperative stay for neonates in our program is not prohibitively long at 9 days. There were 6 symptomatic neonates who were shunted prior to elective repair. One patient had a diagnosis of TOF and AV canal and the others had coronary anomalies that were deemed not suitable for primary repair, such as a large LAD or conal branch crossing the RVOT.

Our current policy is to electively repair patients with TOF at about 4 months of age. Most patients can be managed safely and without complications if an elective repair can be achieved at that time.For younger patients who experience symptoms such as significant cyanosis or acute hypoxic spells, we will attempt complete repair urgently at that time. This includes preterm and low-birthweight neonates. We believe palliation in these patients is a less attractive surgical option than complete repair since shunt operations in smaller patients can result in either higher risk of shunt obstruction if smaller shunts are used or pulmonary over-circulation if larger ones are chosen. In either scenario, patients are not fully saturated and subject to steal from the systemic and coronary circulations.

For patients with TOF and AV canal, our policy is to delay surgery if possible to about 6 to 7 months of age. In our series, patients with this combination were repaired at about a median age of 175 days. Patients with just TOF were repaired at a median of 120 days.

The incidence of postoperative arrhythmias in our program has been previously reported 7. Postoperative JET requiring medical treatment has occurred rarely in our patient population. There are no patients in this series who required placement of a permanent pacemaker for postoperative heart block.

Figure 1. Postoperative length of stay as it is related to age at repair.

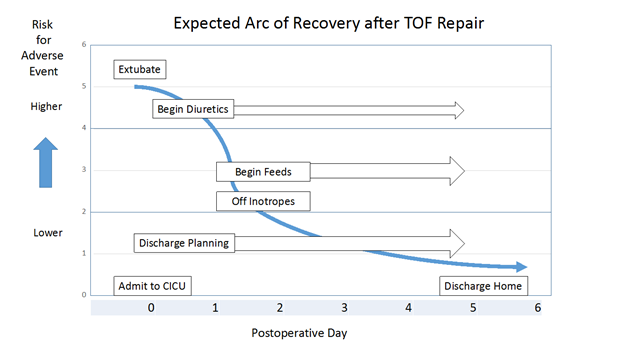

Expected Arc of Recovery:

The expected arc of recovery describes the expected postoperative course for an individual patient after congenital heart surgery. The arc of recovery has been described for patients undergoing repair of TOF and other common congenital heart surgical procedures in the Nicklaus Children’s Hospital CICU Playbook. The playbook includes clinical pathways for patients admitted to our CICU program.

Today, patients undergoing elective repair of TOF (excluding neonates) in our program are usually extubated in the operating room. For those who arrive to the CICU intubated, expectations are for extubation within the first 24 hours. Most patients require little or no inotropic pressor support and arrive to the CICU on an infusion of milrinone, which is usually discontinued in the first 24 to 48 hours after admission. Occasionally, low-dose pressor support is added in the form of an epinephrine or vasopressin infusion. Feeds are usually begun on postoperative day 1 or 2. Diuretics are started when clinically indicated. At the time of discharge, patients often require no cardiac medications or perhaps a diuretic. Discharge is anticipated on day 5 or 6.

Take Home Message:

We present the outcomes of patients undergoing repair of TOF in a single program over a period of greater than two decades. We believe our results are comparable to the very best reported, with extremely low mortality, short length of stay and a low incidence of morbidity. Meticulous surgical technique can reduce the incidence of most postoperative morbidity including the development of tachyarrhythmias or heart block.

You can watch Dr. Burke repair TOF here:

You can watch Dr. Burke repair TOF with AVC here:

Outcomes for cardiac surgical patients at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital continued to be reported in real-time and have been so since 2001. Nicklaus Children’s Hospital’s Real-Time Outcomes is the most comprehensive and transparent outcomes reporting website available today, with over 18 years of outcomes available for review.

References:

- Blalock A, Taussig HB. The surgical treatment of malformations of the heart: in which there is pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary atresia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1945 May 19;128(3):189-202

- Blalock A. The surgical treatment of congenital pulmonic stenosis. Annals of surgery. 1946 Nov;124(5):879.

- Lillehei CW, Cohen M, Warden HE, Read RC, Aust JB, Dewall RA, Varco RL. Direct vision intracardiac surgical correction of the tetralogy of Fallot, pentalogy of Fallot, and pulmonary atresia defects: report of first ten cases. Annals of surgery. 1955 Sep;142(3):418.

- Castaneda AR, Atai M, Varco RL. Technical Considerations in the Correction of Fallot’s Tetralogy. Chest. 1965 Feb 1;47(2):223-30.

- Barratt-Boyes BG, Neutze JM. Primary repair of tetralogy of Fallot in infancy using profound hypothermia with circulatory arrest and limited cardiopulmonary bypass: a comparison with conventional two stage management. Annals of surgery. 1973 Oct;178(4):406.

- Pigula FA, Khalil PN, Mayer JE, del Nido PJ, Jonas RA. Repair of tetralogy of Fallot in neonates and young infants. Circulation. 1999 Nov 9;100(suppl_2):II-157.

- Fishberger SB, Rossi AF, Bolivar JM, Lopez L, Hannan RL, Burke RP. Congenital cardiac surgery without routine placement of wires for temporary pacing. Cardiology in the Young. 2008 Feb;18(1):96-9.

Additional References of Interest:

- Taussig HB. Tetralogy of Fallot: Especially the care of the cyanotic infant and child. Pediatrics. 1948 Mar 1;1(3):307-14.

- Pacifico AD, Kirklin JW, Bargeron Jr LM. Repair of complete atrioventricular canal associated with tetralogy of Fallot or double-outlet right ventricle: report of 10 patients. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1980 Apr 1;29(4):351-6

- Shinebourne EA, Babu-Narayan SV, Carvalho JS. Tetralogy of Fallot: from fetus to adult. Heart. 2006 Sep 1;92(9):1353-9.